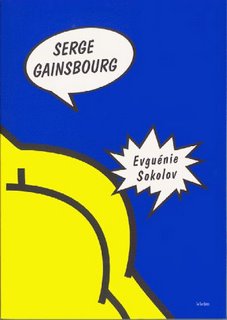

by Serge Gainsbourg

by Serge Gainsbourgtranslated by John and Doreen Weightman

TamTam Books

Like Charles Bukowski, Lucien Ginzburg was a lecherous dog of a man. Blunt, obscene, and, at times, even childish, both were men of pronounced appetites. Born in Germany in 1920 to an American soldier and a German woman, Bukowski came to the U.S. with his family at the age of three; soon the German tongue, which he had heard everywhere in his first few years, began to slip away from his memory. Born in Paris in 1928, Lucien Ginzburg was the son of Russian Jews who had fled the Bolshevik revolution; in time, Lucien’s father changed the family name from Ginzburg to the more French sounding “Gainsbourg,” with Lucien being reborn as Serge Gainsbourg. Bukowski grew up to work a series of dull, boring jobs before finally becoming a writer; Gainsbourg had a similar work history before he began earning his pay as a musician. And although both were controversial, each came to be highly regarded in their respective fields—in Europe, anyway.

Bukowski eventually gained some measure of respect back in the U.S. But Gainsbourg hasn’t quite made it over here, where for a long time he was known only for “Je t’aime... Moi non plus,” his 1969 song which, featuring the orgasmic moans of his then girlfriend, actress Jane Birkin, created a scandal worldwide. As far as America was concerned, Gainsbourg was a one hit wonder.

Across the ocean, however, his fame continued. Gainsbourg went on to romance the likes of Brigitte Bardot, Catherine Deneuve, and Isabelle Adjani, among others. The list of his lovers goes on and on—not bad for a man no one would describe as a pretty boy. But sometimes it was unrequited lust. As in a video from 1985 where Gainsbourg shared a bed with his teenage daughter, Charlotte, and gazed at her longingly through bloodshot eyes as she sang his song, “Lemon Incest.” Or that time when, during a live French television broadcast, Gainsbourg declared, “I want to fuck you” to fellow talk show guest Whitney Houston.

Gainsbourg was, above all, an honest man. Whether you liked it or not, he said whatever was on his mind, and for that the French awarded Gainsbourg the prestigious Croix d’Officier de L’Ordre des Art et Des Lettres. When Gainsbourg died on March 2, 1991, it was something akin to a national day of mourning in France. Because no matter how much he shocked or provoked, his French audience at the very least appreciated and, in many cases, revered him.

Gainsbourg is now becoming more widely known in the United States. But with the dark irony of his songs being lost when left untranslated, it’s no wonder that those who’ve heard only his early jazz inspired pop songs take him simply as a kitschy performer of French “lounge” music. (As it was, Gainsbourg employed, at various times, elements of jazz, African, rock ‘n roll, reggae, rap, even classical music—the melody for “Lemon Incest,” in fact, was a takeoff from one of Chopin’s etudes).

Recent English language covers of his songs by musicians like Nick Cave associate Mick Harvey haven’t helped much in changing the more limited perception of him. So while in France he was considered “on the edge” by young and old alike (at many concerts he performed towards the end of his life, the audience was made up of a majority of teenagers), here he is still seen as an oddball rather than as a “cutting edge” artist. Gainsbourg himself expected as much, and when asked if he had any plans to perform in the U.S., replied, “Why bother? They wouldn’t understand.” Indeed, as Russell Mael of the band Sparks notes, Gainsbourg’s musical satire isn’t easy for many Americans to “get.”

But music wasn’t Gainsbourg’s only means of expression. He was also a photographer, filmmaker, actor, and writer; and in 1980 Gainsbourg published Evguénie Sokolov—his only (and very brief) novel—which has now been reissued here in the U.S. Like much of Charles Bukowski’s work, it presents a first person narrator who’s a little on the rough side, and places him in a rather preposterous situation—the situation here being that Evguénie Sokolov, a painter, has found that his lifelong malady of excessive flatulence has helped him improve his art:

“...while I was testing my mastery by practicing the drawing of sewing needles with a single movement of the pen—a down stroke, then an upward stroke to open the eye, followed by a down stroke to close it—a particularly violent explosion of wind broke a pane in the glass roof, causing my hand to shake like that of an electrolytic child...”

Seeing that farting while in the act of drawing has bestowed “a dazzling beauty” upon his lines, Sokolov builds a contraption out of a bicycle seat and springs. Sitting on this as he draws, Sokolov quickly produces a series of forty “gasograms” and shows them to the most important art dealer in town who immediately gives him a contract. Sokolov’s fame and marketability as an artist rise quickly. He begins having affairs with both women and men, but soon begins to rely more on prostitutes “who attended to my pleasure without my having to worry about theirs.” He also takes to drinking sweet, old-fashioned cocktails (“Lady of the Lake,” “Baltimore Eggnog,” “Corpse Reviver”) to the point where the combination of alcohol and sugar would lead him to stumble into elevators at the hotels he stayed in and “stare, glassy-eyed, at the floor indicator.” Like Gainsbourg himself, Sokolov is a dissolute character whose vices are highly conspicuous. And, like Gainsbourg, his vices play an essential role in the creation of his art.

Although Gainsbourg described his novel as autobiographical, he admitted to “distortions reminiscent of Francis Bacon’s paintings. Evguénie is a guy who knowingly destroyed himself because he wanted fame, and that fame destroyed him.” Among the distortions are Sokolov’s diet of rotten meat and “slightly ‘off’ fish”—a form of sustenance meant to ensure Sokolov’s grand flatulence and his ability to produce his gas-inspired art—and the consummation of his love for Abigail, an eleven year old deaf mute girl. At any rate, one would hope that these are among the distortions.

What can be said with certainty is that Evguénie Sokolov is not a polite work of literature. Real satire seldom is. And although like a great movie epic it evokes emotions ranging from joy to genuine sadness, Sokolov will never be turned into a big budget Merchant-Ivory production. Nor will it ever be offered as a premium by PBS stations during pledge week. What will happen is that is many who read it will be shocked and disgusted—which is exactly what Gainsbourg would have wanted. “For me, provocation is oxygen,” Gainsbourg once declared.

But unlike the self-indulgent provocations of Madonna, for instance, Gainsbourg’s provocations usually had a purpose, a case in point being his song “Aux Armes Et Caetera,” in which Gainsbourg took the French national anthem and transformed it into a reggae song. Disparaging the militaristic themes of “La Marseillaise,” Gainsbourg’s caustic parody upset everyone from politicians to priests. It also went platinum.

Although Gainsbourg’s musical pranks had serious intentions, he could also be ingenuously playful. “Evguénie Sokolov,” the musical counterpart to his novel, is a three minute “song” throughout which Gainsbourg (backed by famed reggae rhythm section Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare) lets loose with a series of farting noises. Obviously, there were aspects of Gainsbourg’s personality which never outgrew adolescence. Which is exactly what made songs like “Harley-Davidson” (“I don’t need anyone on my Harley-Davidson/ I recognize no one on my Harley-Davidson/ And if I die tonight/ It’s my destiny and my right”) so exhilarating. And lurking beneath the self-destructive behavior of Gainsbourg’s Sokolov is a similar exhilaration.

The present reissue of Evguénie Sokolov, while welcome, is not without its problems, the most prominent of which are the obvious typographical errors that occur in the printed text. Nevertheless, this edition of Sokolov will go a long way towards helping those on this side of the Atlantic come to interpret, and perhaps even appreciate, Gainsbourg.

As for helping to define him, that’s another matter completely. In his introduction to Evguénie Sokolov, Dutch writer Bart Plantenga describes Gainsbourg as “one part rat pack, one part beatnik, Chet Baker, Sinatra, a dash of Dylan, Leonard Cohen’s pungent growl, Tom Waits’ irrepressible inventiveness, Johnny Rotten’s naughtiness...” Which goes to show that, considering the wide variety of artists he brings to mind, Gainsbourg himself is extremely difficult to pin down. And to say, for instance, that his one novel (and, to a certain extent, his life) brings to mind the drunken candor of Charles Bukowski is beside the point. Because despite the many things that may have influenced Gainsbourg, he was, above all, his own man. Because whatever it was Gainsbourg took in, it was inevitably his own by the time he spat it back out.

No comments:

Post a Comment